Vilhelm Moberg from Print to Film

Vilhelm Moberg was a Swedish journalist, playwright, and novelist, who lived 1898-1973. During the 1950s, he wrote a series of four novels – “The Emigrants,” “Unto a Good Land,” “The Settlers,” and “The Last Letter Home”— telling the fictional story of a family that emigrated from Sweden to America. The series is so rich and detailed that I can only scratch the surface.

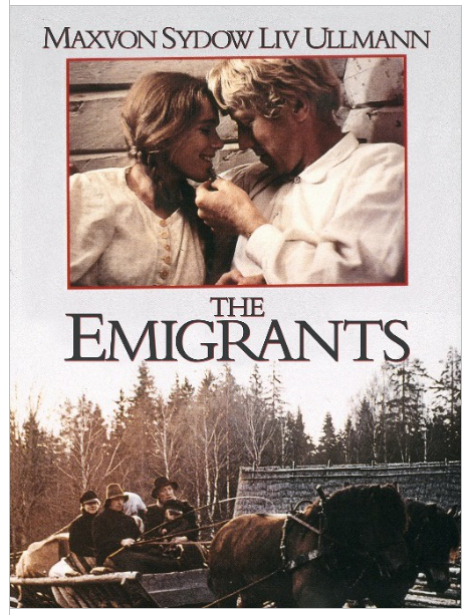

In the early 1970s, Swedish director Jan Troell turned the first two books into one film, “The Emigrants,” and the last two books into another film, “The New Land.” Two famous Swedish actors lead the cast: Max von Sydow as Karl Oskar Nilsson and Liv Ullman as his wife Kristina. Von Sydow appeared in “The Seventh Seal,” “The Greatest Story Ever Told,” “The Exorcist,” and “Game of Thrones.” Liv Ullman appeared in many films directed by Ingmar Bergman.

To see a three-minute interview with Liv Ullman and excerpt from the first film, click here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AQ4UvOczjnw.

You can’t get the first film online due to copyrights, but the second film is available free at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-hqg2hI2Taw. (Note: It runs 3 hours, 22 minutes.)

The story begins in Sweden. In the late 1840s, Karl Oskar Nilsson is a strong-willed young man who lives with his parents, his younger brother and sister. They live on a small stony farm in Småland, like our own Lindgren ancestors, John and Frank Petersson and their sisters Selma and Jenny Petersdotter. (The four siblings dropped their traditional Swedish names and took the name “Lindgren” after they arrived in America.) Karl Oskar marries Kristina Johansdotter and they start a family. Hardships come soon. Heavy rains ruin the wheat crop, the potatoes go rotten, livestock must be sold to pay the mortgage, and they sink deep into debt.

They are reduced to eating “famine bread,” a mixture of flour, chaff, and ground up acorns. The ruling class does nothing to help. Kristina screams at Karl Oskar’s blasphemy when he throws a pitiful handful of wheat in the air and asks God to take it all. After their daughter dies a horrible death and lightning strikes their barn, they are ready to leave Sweden.

The priest and sheriff govern the parish, and the peasant farmers are expected to obey their masters who own the land, without complaint. Karl Oskar and his brother Robert make plans to go to America. Kristina’s Uncle Daniel preaches to a small communal religious group that meets illegally in his house. (Lutheranism is the State religion.) After suffering repeated persecution, Daniel throws in his lot with Karl Oskar. Daniel is inspired by the Biblical story of the Jewish exodus out of Egypt.

Karl Oskar’s decision to emigrate is seen as an insult to the parish. The parish community has lived on the same land for generations. His neighbors think he thinks himself better than they are. He feels shamed by the parish priest for having to ask hat in hand for permission to leave and having his decision announced publicly in church.

Moberg shows the deep faith of the emigrants, as well as their connection to the earth. Jonas Petter leaves his wife behind and takes every opportunity to tell bawdy stories. Daniel’s follower Ulrika is a profane former prostitute who eventually becomes Kristina’s best friend.

In the year 1850, Karl Oskar and his family and Uncle Daniel’s group travel to the seaport of Karlshamn to board a small, crowded sailing ship. (Ocean-going steamships came later.) Their Atlantic passage is like that of Amy Johnson Lindgren’s parents, J.P. Johnson and Johanna Dorothea Burman. Diseases like cholera, dysentery, small pox, and typhus run rampant, and there’s no doctor on board. Several emigrants, including Daniel’s wife, die at sea – their bodies wrapped in sailcloth. Each gets a funeral service by Daniel and a scoop of Swedish earth before dropping into the sea. Ten weeks pass before land is sighted. (By 1870 a steamship passage took less than two weeks.)

For the second book, “Unto a Good Land,” Moberg took his title from the Bible: “For the Lord thy God bringeth thee unto a good land.” Karl Oskar and his group travel by railroad and steamboat from New York to Chicago. (By the late 1860s, when J.P. Johnson and Johanna Dorothea Burman left, emigrants could take trains that connected all the way to Chicago.)

After they reach Chicago, Karl Oskar’s group make their way to Minnesota by steamboat and horse-and-wagon. Karl Oskar insists on walking for miles until he finds the best spot to settle on, about forty miles northeast of Minneapolis, where the topsoil is three feet deep.

In the third book, “The Settlers,” Karl Oskar builds a cabin for his family, clears land, and plants wheat. Kristina is sometimes overcome with homesickness. The nearest town is far away and the weather changes quickly. One day Karl Oskar takes his son Johan to town with him to sell grain, but gets caught in a blizzard. How to save his freezing son’s life? Karl Oskar kills the ox that pulled their wagon. He guts the ox and puts his unconscious boy in the warm carcass, leaving a breathing hole near the boy’s mouth.

This scene is based on a true story Moberg found in his research. In “The Empire Strikes Back,” George Lucas has Han Solo kill a “tauntaun” creature in the same way to save Luke Skywalker. More recently, Leonardo DiCaprio’s character guts a dead horse and gets inside the carcass to survive a blizzard in “The Revenant.” It has become a Hollywood “trope.”

“The Settlers” tells the story of the younger brother Robert and his friend Arvid, who leave Karl Oskar to join the California Gold Rush. The naive boys go to St. Joseph and travel overland going west. They drive donkeys for a Mexican who gives them his gold coins before dying from yellow fever. Director Jan Troell shows them struggling under a blazing sun, accompanied by an eerie soundtrack. Arvid dies and Robert falls in with a dishonest Swede who swindles him. Robert returns to Karl Oskar and Kristina emaciated with saddle bags full of worthless banknotes.

In the fourth and last book, “The Last Letter Home,” Kristina has had increasingly difficult pregnancies. A doctor warns that her next child could cause her death. Nevertheless, she decides to conceive another child with Karl Oskar and subsequently dies in childbirth. A sub-plot of this last book is the Sioux uprising during the Civil War, followed by the horrible mass hangings of Indians in Minnesota.

Karl Oskar grows old and visits Kristina’s grave often. He sits in his cabin, vividly remembering Kristina walking down a path to him, when she agreed to marry him. The film ends with the voice-over of a letter written to his sister in Sweden, telling of his death. The camera then shows Karl Oskar dressed formally and pulls back to reveal a large photograph of the extended family – Karl Oskar and Kristina, their children, in-laws, and many grandchildren.

A remake of Jan Troell’s first film, “The Emigrants,” will open in Swedish movie theaters on Christmas Day, 2021. There’s no word yet about a release date for the U.S. To see the trailer, click on https://cineuropa.org/en/video/411614/

Editing support from Linnae Coss