For centuries, Sweden had a tightly-knit population. The Lutheran State Church carefully created and preserved records. Genealogists have traced Swedish ancestors back to the 1600s and beyond. Generations of Lindgren and Johnson ancestors lived in the Jönköping and Kronoberg districts of Småland. Many people didn’t travel more than 30 miles from their home villages in their whole lives.

Swedish society was made up of four major classes: nobles, clergy, townsmen, and peasants. The first three classes were five percent of the population. The other 95 percent were peasants. The peasant class was composed of three sub-classes: landowners, tenant farmers, and laborers. The landowners planned to extend their holdings and the tenants hoped to start their own farms. The laborers were often sons and daughters of tenants. The landowners had a stake in Sweden but the others did not.

As the Swedish population grew, a market form of agriculture began to replace subsistence farming. For centuries agriculture had followed feudal traditions. Community land had been divided into strips and patches. Each peasant might have more than 60 disconnected sections of land to cultivate. As the little sections of land were exchanged and joined into larger units, many tenants were uprooted from their old homes and forced to move miles away. After moving short distances, it was easier for peasants to consider moving again. They could go to Swedish cities or even immigrate to the U.S.

In the early 1800s, the government passed laws that consolidated and enclosed the land in an attempt to increase food production. The reforms were designed to strengthen the national economy, but agricultural changes moved slowly. By 1850 the process of consolidation was only half completed.

The peasant class became more divided as prosperous peasants bought more land and increased their wealth, while those with little or no land got poorer. The agrarian reforms created a breeding ground for potential emigrants. One historian claimed that the destruction of the feudal land system in Sweden did more to stimulate emigration to the U.S. than any other single factor.

Another reason to emigrate was religious persecution. The Lutheran State Church of Sweden had grown lax and corrupt by 1850. Lutheran pastors made brännvin, a liquor distilled from potatoes or grain, and sold it to their congregants. Pious Swedes abstained from alcohol. They held illegal church services outside or in their homes. Officials broke up such meetings and fined the members or put them in jail. Pious Swedes also objected to illegitimate children born to unwed mothers. Faithful Swedes wanted to worship in America, where they could express their beliefs in their own way.

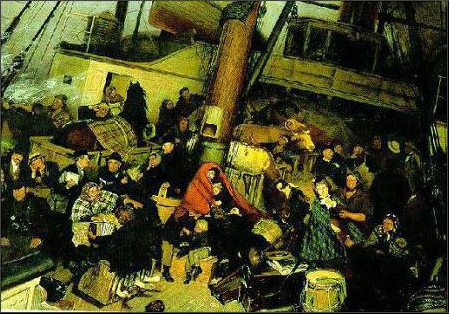

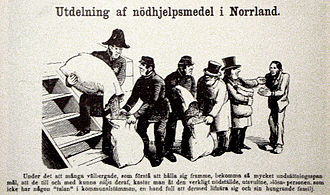

Another reason to emigrate was three consecutive years of famine, which Aunt Nellie called “The Hard Years.” A harsh winter in 1867 led to poor harvests, starving livestock, and high prices. The following two years brought drought and famine. Some government officials advised hungry people to eat bark bread made from lichen. National supplies of flour went mostly to the upper classes; some trickled down to the poor. John Peter Johnson and Johanna Dorothea Burman immigrated with separate groups in the late 1860s. They met in Altona, Illinois and married there.

Peter Gustav Magnusson, his wife Ingrid and their children, Amanda, John, Frank, Ida, Selma and Jennie, lived in Kronoberg at Norratorp (the north farm). Norratorp consisted of 14.28 acres of land on the Lågan River, but just nine or ten acres were tillable. John and Frank Petersson were in the third wave of immigration. They changed their names to Lindgren when they immigrated to America in the early 1890s.

All of these “push” factors prepared Swedes to leave their country. Stories and letters about freedom and abundant land were “pull” factors that drew Swedes to America.